//Feminist//: a person who advocates for women’s rights based on equality of the sexes.

We’ll get into it in a second. I'm not in the breakthrough generation anymore, and my language around feminist issues has undergone a lot of change. Once upon a time, white women in sports were the observable minority, because women of colour had even less prominence in the world conversation. Observing my own writing as a "white female voice" was never something I considered before recent times.

Our standards for language in Western English are changing, and it's clear that many people regard some of these changes as an attack. The key thing to remember, is that asking you to adapt your personal etiquette to include everyone is never an attack - it's just good manners. Of course, you have a choice over whether you use your manners or not - but if we can start calling a woman "Mrs" instead of "Miss", I really think we can cope with the pronouns people prefer. I've had to learn some words - "cis" means you identify as the gender assigned to you at birth. Super easy. However, the rhetoric around transgender women and men in sport is complicated, and so valuable it needs another blog post by itself. What I want to talk about now, is the dialogue about women in general (which includes cis and transgender women), and feminism in particular.

A couple of basics, because I'm going to talk about some stuff that's super familiar to me. But that's after years of figuring out how I want to verbalise my thoughts on feminism (and having some really good friends who've challenged me and helped my dialogue improve). I’d like to add – this is a personal blog. It’s up to you if you read it, and what you’re reading is my personal interpretation of feminism. So:

- Paradigm. A paradigm is a typical pattern or model of something, such as a stereotype, that is often informed or strengthened by cultural belief. For a really basic example, this could be as simple as a stereotypical, ideological gender role: a woman staying home after giving birth to look after kids. It can be a practical arrangement - if one parent works to make money, the other can stay home to look after a dependent. However with modern infrastructure, this doesn't have to be a female specific role. A man can also stay at home to look after kids, while the woman works. This is a good change from the previous normal social arrangement, because it offers women the choice to either stay at home and look after kids, or proceed with a fairly uninterrupted career. Neither is the wrong choice. However, a cultural belief that specifically women should stay at home with the kids omits choice. A person who wants to work, but cannot, due to cultural beliefs outside of their control, has had a choice about their own life removed. I don't think I need to go into why that's impractical for everyone, but if I do, let's leave it at: it's a choice about your own life, which all sexes should have. A woman who has children and decides to raise them for 18 years, to me is as much a feminist as a woman who wants to have kids and immediately return to work.

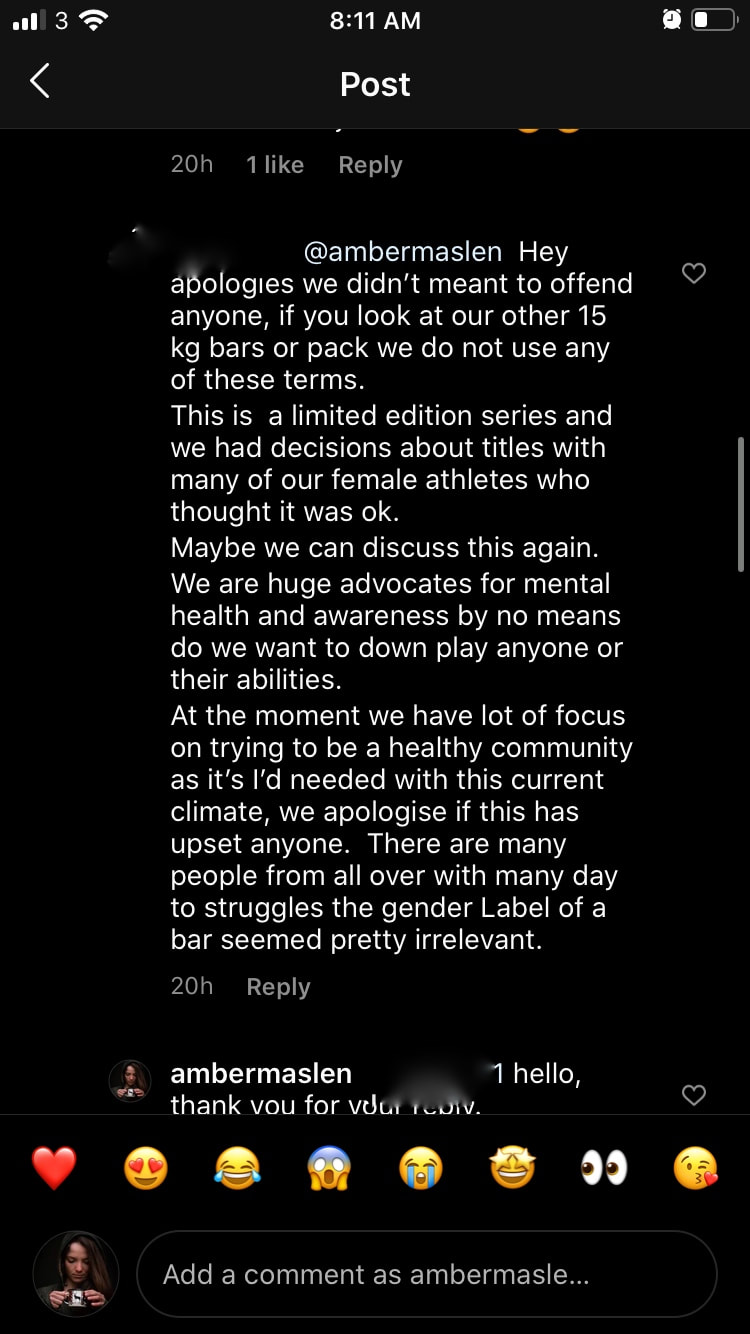

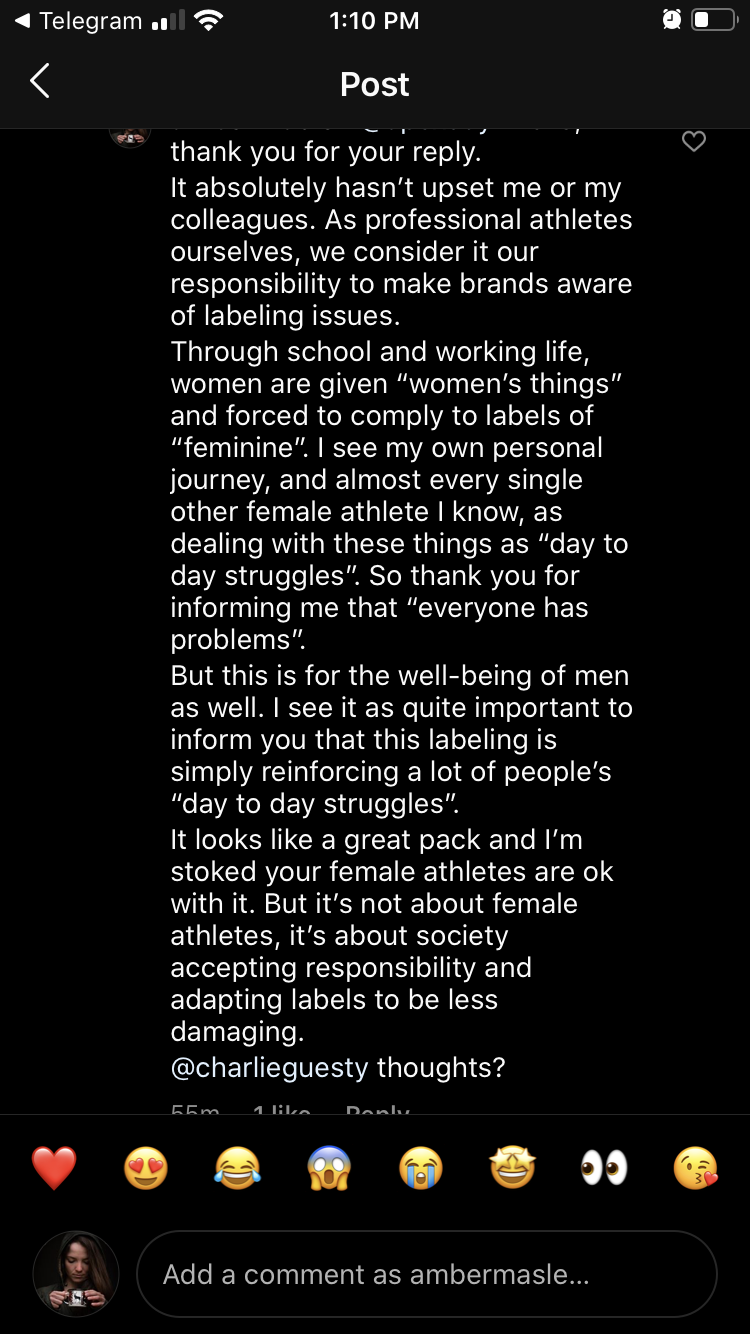

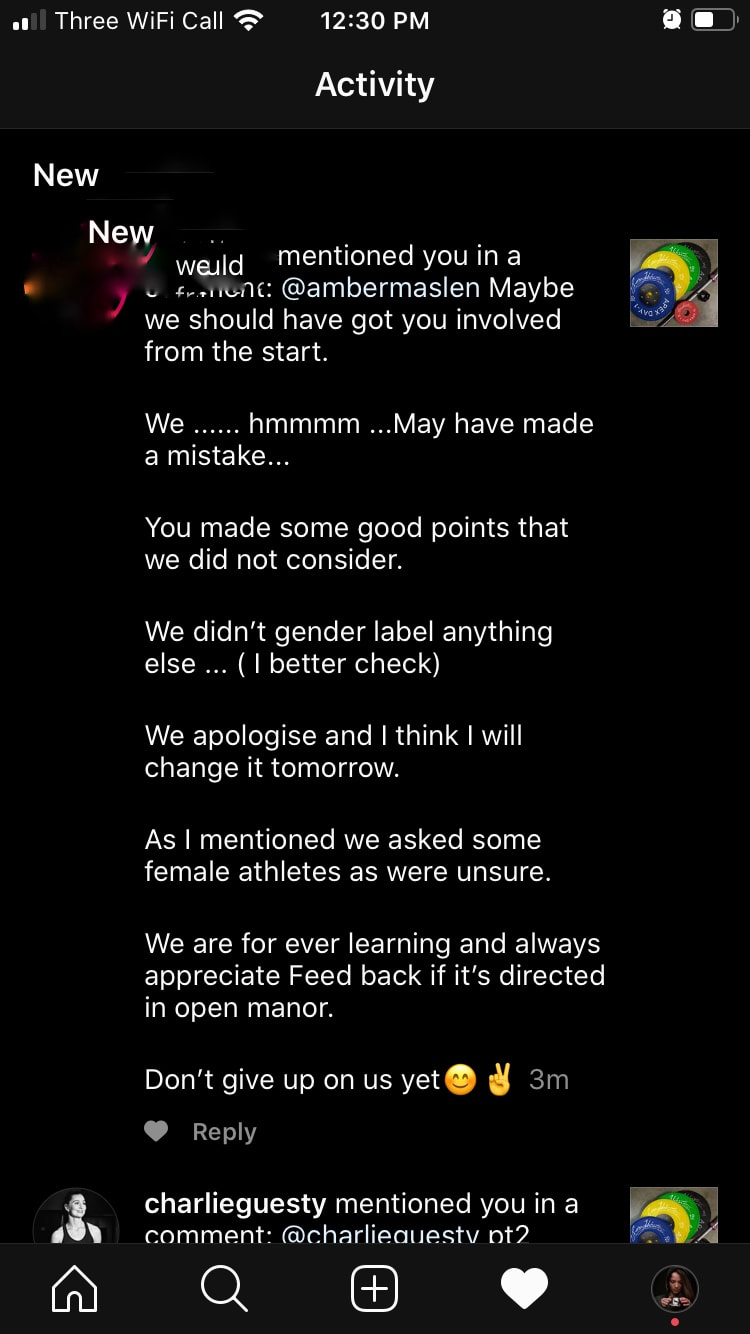

- Language norms / standards. Civilisations have been built and destroyed by words. If the cavemen hadn't started to talk to each other to make effective teams, and then learn new languages to communicate and start trading with other hominids, we would still be swinging around in trees. The words we use daily reflect the particular culture in which we exist. If we tell a man from the moment he understands words that he needs to be strong and confident, but he doesn't identify with either of those things, we have a problem. If, through words, social norms build you a checklist of things to tick that give you an identity, and you can't tick all those boxes, where does that leave you? Probably feeling pretty bad. Maybe uncertain of where you fit in, in a culture that doesn't seem to offer you any other boxes to tick. Humans are extremely social animals, and we know from history that excluding people results in depression, illness, and death. It is only simple, innocent, "harmless" words that can create a welcoming environment for somebody, or a harsh, hostile one. This is why people get so upset about language. It builds and reinforces those ideologies we just talked about - which can catastrophically alienate any humans who don't or can't fit into those boxes.

I've grown up in a sport that's been male dominated for most of my career. Kayaking in general, and slalom in particular, has taken some huge leaps. We're now gender equal at the Olympic Games, and while there are certainly still problematic observable inequalities, we have exceptional role models such as Jess Fox dominating the headlines and making it easier for young women to see themselves in the picture. On a broader kayaking stage, Nouria Newman has made leaps for women across whitewater, overcoming obstacles to become one of the greatest paddlers in history. When I was younger, there were coaches and friends who repeatedly made observations that "female sport is easier to succeed in". It's not a healthy rhetoric, because it devalues the women who have succeeded and those who are still striving, and I'm happy to see how much it's changing. Britain's most successful canoe slalom athletes are women, they're from the same generation as me, and they've overcome this rhetoric to be dominant on the world stage.

So, what's this discussion about, if we're all good? Things are changing for sure. But we're in a weird time just now, where many voices seem to think that raising up a group of marginalised people will damage the established "normal". For the sake of discussion, I'm talking about the response to "feminism" in many kayaking groups across the US and Britain. Because this discussion requires absolute transparency, I'm talking about men AND women feeling like "feminism" is a bad, or anti-male thing. Recently on social media, a popular kayaking meme page came under fire for sexist jokes. Maybe I'm making a huge mistake in reflecting on this - but hear me out.

As Frankie Boyle once said, everything's funny until someone finds something extremely personal to them. Humour, and especially British humour, is cynical and steeped in irony. Can it be in poor taste? Totally. Does it require people to take a second to remember the other jokes they laugh at, often at the expense of others? Resoundingly yes. Comedy and laughter is a form of revolution - it juxtaposes common social norms against personal values, and ridicules them. Often dark humour and comedy make a mockery of well-established prejudices, to highlight the ridiculousness of something we may not consciously observe in day-to-day life. I personally feel that day-to-day, non-ironic, aggressive or sexist language about women is dangerous. I also feel that sexist jokes making an ironic dig at stereotypical, socially constructed characteristics of women, is not necessarily dangerous. To make my point, in many instances, humour is doing some legwork to deconstruct those stereotypes.

It was incredible to read some fluent, educated responses to sexist jokes from extremely well-known athletes on the page. I was truly inspired - it's simply not something that would have happened ten years ago, famous male kayakers making a stand for women in a linguistic and social sense. Calling out sexist language isn't necessarily an attack on the creator - but it is important to have the discussion, even if just one more person becomes aware of the effect that day to day, aggressive language against women has. I'm so proud of my sport, and the men in it, for stepping up to the bar. What breaks my heart, is to see strong feminist standpoints not only being shot down as "extremist", but also being dividers for our community. Did I take offence to the jokes? No, not at all. Did I love the comments that were in favour of reinforcing positive language around women in sport, rather than joking about it? Yes, I loved that too. What I truly HATED, was that a strong stance made a whole bunch of people feel like they don't belong in the world of feminism.

Feminism is for literally everyone. Of course, you get extremism and bad manners in every camp. But for me, if you can tick a box that says "yes, I believe everyone regardless of genitals are of equal value as human beings", then you are a feminist. Female worth is not based on fulfilling a stereotypical female role. Male worth is not based on checking boxes that society has created for them. The same applies for literally every human being - your contribution to the world does not have to be greater than the masses in order to qualify your space on the planet if you're from a minority group. Still today, women, POCs, and the LGBTQIA+ community must over-achieve in many ways for an equitable amount of recognition. For a mother to return to work to pursue her career, and it be deemed an "acceptable" compromise to the normal role, she has to be a brain surgeon. Is that reasonable? No. To have a voice that is actually, truly heard, do these groups need to shout louder? Yes. Do we communicate best when shouting? No, not always.

It's a complicated dialogue, but it's worthwhile doing the legwork. There isn't a single person alive who doesn't interact in a meaningful way with someone from a minority group - your parents, siblings, colleagues, friends, the company you work for. Society as a whole is built on the back of humanity. We're incredibly diverse, and without our diversity we wouldn't have evolved to our current state of existence. Personally, I'm stoked to be here. To divide ourselves in a way that we're in complete control of is a huge mistake. Humour is part of how we have self-governed, resisted insidious ideologies, and created passion for current issues for centuries. I'm not saying don't take offence, for sure. But it's quite important to try and understand why you're offended. If it's language that makes you feel unsafe, we have a far better voice when we consider exactly why, and can make a fluent point about it. Basically, figure out a way to use your words to their best effect. Sometimes it might have to go as far as shouting – but usually there’s a way to get more people to listen. Should we have to? No. Do we need to? Yes.

Hopefully, after reading this, someone who previously may have heard "feminism" and run screaming for the hills, might think that actually, it's not such a bad word. You don't need to say it, or use it, or put it on your bio. But people do love to throw around boxes for you to tick. Just because you don't tick a certain box (which I've never been very good at), doesn't mean your core values are in question. If you tick a box that says, "my respect for people is not determined by their gender", then that's good enough for me.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed